In this section, we first explain what prenatal testing is. Then, we explain the reasons prenatal testing is offered, and why people do it or not. Finally, we describe the various types of prenatal testing.

What is prenatal testing for Down syndrome?

What are the reasons to have prenatal testing for Down syndrome?

-

- Why is it offered and is it mandatory?

- Why do people do it or not?

How is prenatal testing for Down syndrome done?

-

- Prenatal screening

- Nuchal translucency (NT) scan

- Serum screening

- Non-invasive prenatal screening (NIPT)

- Prenatal diagnosis

- Amniocentesis

- Chorionic villus sampling (CVS)

- Prenatal screening

What is prenatal testing for Down syndrome?

Here are the terms you need to know when you make decisions about prenatal testing.

| Term | Definition |

| Prenatal | Prenatal means “before birth”. All the tests that are discussed on this page are done in the first half of pregnancy. |

| Down syndrome | People with Down syndrome have delayed intellectual and physical development. Most children with Down syndrome learn to walk and talk. They also learn to take care of their basic needs. However, it usually takes them longer to get there. Many children with Down syndrome attend regular schools. People with Down syndrome live until about 60 years old. They can have health issues such as heart defects. Most people and families living with Down syndrome report being happy. Adults with Down syndrome can live alone, with their parents, in group homes or in residences. Most need some type of supervision. For more information, check out the “Down syndrome” section. |

| Prenatal screening for Down syndrome | A test that tells you if your baby as a or a low chance of having Down syndrome. There is no risk of losing the baby with prenatal screening. It requires a blood test and/or an ultrasound. |

| Prenatal diagnosis for Down syndrome | A test that tells you if your baby has Down syndrome or not. There is a very small risk of miscarriage with prenatal diagnosis. It requires collecting samples from inside the womb with a needle. |

| Prenatal testing for Down syndrome | Prenatal screening and diagnosis for Down syndrome. |

| Positive prenatal screen for Down syndrome | When prenatal screening says that your baby has a high chance of having Down syndrome. |

| Negative prenatal screen for Down syndrome | When prenatal screening says that your baby has a low chance of having Down syndrome. |

| Positive prenatal diagnosis for Down syndrome | When prenatal diagnosis says that your baby has Down syndrome. |

| Negative prenatal diagnosis for Down syndrome | When prenatal diagnosis says that your baby does not have Down syndrome. |

What are the reasons to have prenatal testing for Down syndrome?

Why is it offered and is it mandatory?

There are common beliefs about reasons for prenatal testing. Here is a list of beliefs and realities about prenatal testing.

| Belief | Reality |

| Prenatal testing is mandatory | Prenatal testing is offered to all pregnant patients but it is not mandatory. |

| Prenatal testing is recommended by doctors. | Doctors offer prenatal testing to all pregnant patients. It is a personal choice whether to do it or not. |

| Prenatal testing is part of the “routine” pregnancy follow-up. | Prenatal testing is “routinely” offered. However, it is a personal choice whether to do it or not. |

| The government pays for prenatal testing. This means that it is better to do it than not. | The government pays for prenatal testing to ensure equal access for those who want to do it. It does not mean that it is better to do it than not. |

| Prenatal testing aims to get rid of Down syndrome by aborting all the babies with Down syndrome. | The goal of prenatal testing is to offer information to pregnant patients. Based on this information, some pregnant patients do choose to end the pregnancy. Others use the information to prepare in advance for raising a child with special needs. Some couples plan for adoption. |

| Prenatal testing for Down syndrome is the most common kind of prenatal testing because Down syndrome is the worst condition a baby could have. | Testing for Down syndrome is more common and has been done for longer. This is because Down syndrome is easy to identify in the lab. It is not because it is worse than other conditions a baby could have. |

| I should do everything that I can to avoid having a baby with Down syndrome. | This is a personal choice. There is no right or wrong answer. There is no “should”. People with Down syndrome and their family are usually happy. |

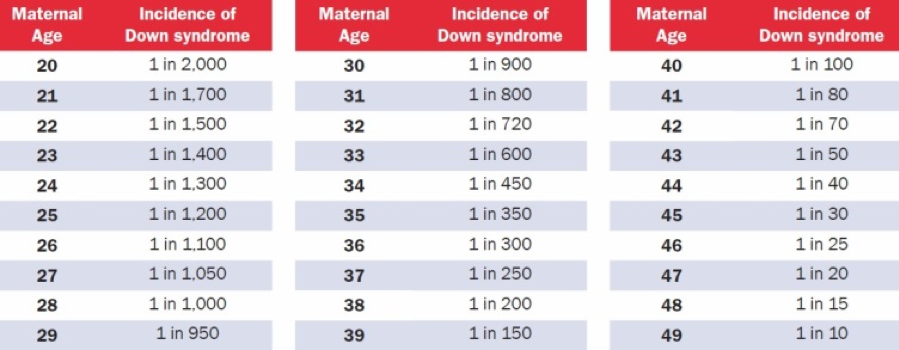

| My chances of having a baby with Down syndrome are higher because I am over 35 years old. This means that I should do prenatal testing. | It is true that the chances of having a baby with Down syndrome increase with age. Yet, babies with Down syndrome are born to mothers of all ages. No matter how old you are, it is always a personal choice to do prenatal testing or not. |

| I will have to do prenatal diagnosis if I get a positive prenatal screen. | A positive prenatal screen does not mean that you have to do prenatal diagnosis. It is a personal choice. After a positive prenatal screen you may: – choose to stop testing and continue the pregnancy. For people with a positive prenatal screen who wish to terminate the pregnancy if the fetus has Down syndrome, confirming the results with prenatal diagnosis is strongly advised. |

| I will have to terminate my pregnancy if I get a positive prenatal diagnosis. | A positive prenatal diagnosis does not mean that you have to terminate the pregnancy. It is a personal choice. |

| Prenatal testing is a good way for me to feel reassured that my baby does not have intellectual disability. | Down syndrome accounts for 6 to 8 in 100 cases of intellectual disability. In other words, most cases (92 to 94 in 100) of intellectual disability have other causes. Therefore, negative prenatal testing does not mean that a baby will be “typical”. For instance, there is no prenatal testing for autism. |

Why do people do it or not?

There are many reasons for people to choose to do prenatal testing. There are also many reasons for people to choose not to do it. There is no right or wrong choice.

| Reasons for doing prenatal screening | Reasons for declining prenatal screening |

| If my baby has Down syndrome, I will make changes to my birth plans. If my baby has Down syndrome, I prefer to prepare in advance. If my baby has Down syndrome, I prefer to arrange for an adoption. If my baby has Down syndrome, I prefer to terminate the pregnancy. I am not decided about the above. I prefer to think about this only if my baby has Down syndrome. | I would not change my birth plans because of Down syndrome. I do not feel the need to prepare in advance for a baby with Down syndrome. I would not choose adoption because of Down syndrome. I would not choose to terminate my pregnancy because of Down syndrome. I do not want to be stressed about the results. I want a less medicalized pregnancy. I am opposed to prenatal screening for philosophical or religious reasons. |

| Reasons for doing prenatal diagnosis after a positive prenatal screen | Reasons for declining prenatal diagnosis after a positive prenatal screen |

| I want to know for sure if my baby has Down syndrome. I do not want to worry for the rest of my pregnancy whether my baby might have Down syndrome. I will end my pregnancy if my baby has Down syndrome. | I do not want to risk losing my baby. I do not want an invasive test. I do not want to terminate my pregnancy. |

It is important to understand why prenatal testing is offered specifically for Down syndrome (Trisomy 21). This emphasis on Down syndrome is not because it is the worst condition a child can have. It is also not because people living with Down syndrome do not have a good quality of life or a ‘life worth living’. In fact, many people who have first-hand experience with Down syndrome do not consider it to be something that needs to be avoided.

-

-

- The first reason testing for Down syndrome is offered is that it is possible. The genetic basis of Down syndrome (3 rather than 2 chromosomes 21) is easy to identify and it is well researched and understood. This is not the case with most other causes of intellectual disability or other congenital anomalies. There are other conditions that are easy to diagnose during pregnancy, such as , , and . These conditions are often screened for at the same time as Down syndrome.

- The second reason for the emphasis on Down syndrome is that of all the known causes of intellectual disability, it is the most common. Yet, if we consider all the other causes taken together (combined), then they are responsible for 92-94% of the cases of intellectual disability. In other words, Down syndrome is responsible for about 6-8% of intellectual disability cases. This means that terminating a pregnancy on the basis of Down syndrome does not eliminate the probability of having a child with an intellectual disability.

-

The purpose of prenatal testing is to identify the presence of Down syndrome in the fetus. Parents may choose to use this information for various reasons:

-

-

- They may want to have this information because it involves an increased risk of complications during delivery. They may want to change their plans for the birth (for example, have the baby at the hospital rather than at home).

- They may want to have this information to prepare in advance for the birth of a child with Down syndrome (for example, read about Down syndrome, find out about available services, and connect with support groups).

- They may want to have this information because they prefer not to have a child with Down syndrome and would choose to terminate the pregnancy if the fetus is diagnosed with it.

- They may want to have this information because they would continue the pregnancy but would like to make plans for the child to be adopted.

-

To learn more about the possible pregnancy decisions after a positive diagnosis, click here.

Whatever the reason, pregnant patients should always be offered prenatal testing. They should never be pressured or guilted into doing or not doing it.

Choosing to use prenatal testing or not to use it, is a personal decision. Pregnant patients may want to make this decision alone, or with their partner. They may wish to discuss it with friends, family members and/or health care providers. The role of health care providers in prenatal testing is to provide all the information and counseling necessary for the pregnant patient/couple to make their decision.

The fact that prenatal testing is routinely offered and the fact that some tests are paid for by the Canadian public healthcare system (or by the government or insurance in other countries) does not mean that it is better to use them than not to use them. Prenatal tests are tools that are made available to pregnant patients to help them make choices that suit their needs and preferences. Choosing not to use these tools is as valid as choosing to use some of them or all of them.

How is prenatal testing for Down syndrome done?

Prenatal screening

Prenatal screening is a test that tells you if you baby as a high or a low chance of having Down syndrome. There is no risk of losing the baby with prenatal screening. It requires a blood test and/or an ultrasound. There are three types of prenatal screening: Nuchal translucency scan, serum screening, and non-invasive prenatal screening (NIPT).

Learn more about probabilities (chance)Prenatal screening methods used together or separately, give a chance of the fetus having Down syndrome. This chance is described as ‘high’ or ‘low’. The cut-off between ‘high’ and ‘low’ varies between programs but it is generally around 1/300.

To understand probabilities better, it can be useful to present them in various forms.

For example:

-

-

- A 1/300 probability that the fetus has Down syndrome means that in a group of 300 pregnant patients, one will have a fetus with Down syndrome.

- A 1/300 probability that the fetus has Down syndrome also means a 299/300 probability that it does not have Down syndrome. Therefore, it means that that in a group of 300 pregnant patients, 299 will not have a fetus with Down syndrome.

- A 1/300 probability that the fetus has Down syndrome means a 0,3% probability that it has Down syndrome and a 99,7% probability that it does not.

-

The cut-off points for probabilities to be considered ‘high’ or ‘low’ are set with the intention of maximizing detection rates while minimizing false-positive rates. The detection rate is the proportion of babies with Down syndrome that are given a “high-chance” result. The false-positive rate is the proportion if babies without Down syndrome that are given a “high-chance” result.

It is useful to understand this because many people experience anxiety when they hear that they have a “high chance” after screening. Calling the result “high chance/risk/probability” can be misleading. Most people would consider that if an event has a 1 in 250 or 1 in 300, or even a 1 in 100 chance of occurring, it is not “highly likely” that this event will occur. Indeed, a large majority of those who get a “high chance” result after nuchal translucency scan or serum screening do not carry a baby with Down syndrome. Less than 5% of fetuses with a positive serum screen actually have Down syndrome. This is called the “positive predictive value” (PPV).

A 5% positive predictive value means that a pregnant patient who has received a “high chance” result that the fetus has Down Syndrome has a 5% chance that the fetus does have Down Syndrome and 95% chances that the fetus does not have Down Syndrome.

Interpreting a risk/chance level is very subjective and personal. Different people may have very different understandings and feelings about what is an acceptable risk for them.

Individual patients may decide for themselves what they consider to be high chance/risk/probability. Based on this, they may pursue follow-up options (diagnostic testing) or not, depending on their own tolerance of risk. However, public prenatal testing programs do set eligibility criteria. Consider the following examples.

-

-

- Mary’s fetus has been identified as having a 1 in 30 chance of having Down syndrome. Mary finds this probability quite high. The public health system in her province has a cut-off point at 1 in 300. Mary will be eligible for further testing in the public system and will pursue it. Depending on the province she lives in, she may have free access to NIPT before she is offered diagnostic testing (amniocentesis).

- Lucy’s fetus has been identified as having a 1 in 350 chance of having Down syndrome. Lucy finds this probability quite high. The public healthcare system in her province has a cut-off point at 1 in 300. Lucy will not be eligible for further testing in the public system, but she will pursue further testing privately and pay for it out-of-pocket.

- Chloe’s fetus has been identified as having a 1 in 250 probability of having Down syndrome. Chloe finds this probability quite low. The public healthcare system in her province has a cut-off point at 1 in 300. Chloe would be eligible for further testing in the public system, but she chooses not to do any more tests.

-

It is also important to consider that the type of results provided by screening never completely eliminates the probability of the fetus having Down syndrome. For instance, when the screening result is 1 in 25 000, it still means that out of 25 000 pregnant patients with this result, 1 is indeed carrying a fetus with Down syndrome.

A diagnostic test is required if a person wishes to completely eliminate the uncertainty regarding Down syndrome. In this case, the probability of the fetus having Down syndrome needs to be weighed against the risk of a miscarriage occurring because of the diagnostic test. Statistically, this risk of such a miscarriage is estimated between 1 in 200 (0.5%) and 1 in 500 (0.2%). In addition to the probability of each event, people may consider which event they wish to avoid the most – a miscarriage or the birth of a child with Down syndrome. There is no right or wrong answer to this question. It is very personal.

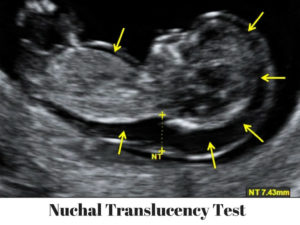

Nuchal translucency scan (NT scan)

The NT scan is an ultrasound that looks at the neck of the baby. It measures a layer of fluid that all babies have at the back of their neck. When the there is more fluid, there is a higher chance that the baby might have Down syndrome.

The NT scan is done between week 11 and week 13 of pregnancy. It is often done with serum screening. Out of 100 babies with Down syndrome, this type of prenatal screening will find about 85.

If your NT is positive, your doctor will offer you NIPT and/or prenatal diagnosis.

The NT scan can also detect signs of trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 and heart defects.

Learn more on NT scansOther body features of the fetus also provide useful information at this point. For instance, the absence of a nose bone is also an indicator for a higher probability of trisomies. In addition, some organs can be visualized, the heartbeat can be heard, and the fetus can be measured to monitor fetal development.

Serum screening

Serum screening is a blood test that detects signs that the baby has Down syndrome. This test measures hormone and protein levels from the baby and placenta.

Some programs use a single blood draw in the first trimester. Others also use a second blood draw in the second trimester. The first sample is taken at week 10 to 13. The second sample is ideally taken 3-4 weeks later, at week 14 to 16. It can be done until week 20.

Serum screening also detects signs of , and .

Serum screening is often done with the NT scan. Out of 100 babies with Down syndrome, this type of prenatal screening will find about 85.

If your serum screening is positive, your doctor will offer you to take NIPT and/or prenatal diagnosis

Learn more about serum screeningDifferent screening programs and different physicians offer various combinations of the first and/or second trimester serum screening with NT scan and/or NIPT. Using the second trimester serum screening has the advantage of making the results more accurate, and the disadvantage of delaying the results of screening.

A few examples:

A combination called “Enhanced First Trimester Prenatal Screening” uses the first trimester serum screening and the NT scan. It gives a result in the first trimester with an and . If a pregnant patient ‘screens positive’, it means that she is given a ‘high chance’ result based on this screening combination. In this case, the patient may access NIPT or prenatal diagnosis in the first trimester or early in the second trimester. This screening combination is offered by the Ontario and Saskatchewan public programs, as well as in private clinics across Canada.

Another combination called “Serum Integrated Prenatal Screening” uses the serum screening from the first and second trimesters. It gives a probability result in the second trimester with an and a . If a pregnant patient ‘screens positive’, it means that she is given a ‘high chance’ result based on this combination. In this case, the patient may access NIPT or diagnostic tests later in the second trimester. The Serum Integrated Screen is offered by the Quebec and British Columbia public program and by private clinics across Canada.

A third combination called “Integrated Prenatal Screening” uses the serum screening from the first and second trimesters with the NT scan. It gives a probability result in the second trimester with an and a . If a pregnant patient ‘screens positive’, it means that she is given a ‘high chance’ result based on this combination. In this case, the patient access NIPT or diagnostic tests later in the second trimester. The Integrated Screen is offered by the Quebec and British Columbia public program, in locations where nuchal translucency is available, and by private clinics across Canada.

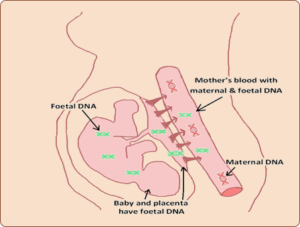

NIPT

NIPT stands for “non-invasive prenatal testing” and it tests cfDNA which means “cell-free DNA”. Pregnant patients have little bits of DNA from the placenta in their blood. This DNA is a lot like the baby’s DNA. NIPT test looks at this cfDNA to identify fetus with a high chance of having Down syndrome.

You may know NIPT under a different name:

-

- NIPS (Non-Invasive Prenatal Screening)

- cfDNA screening

- Commercial names : Panorama, Harmony, Verify, and others. (None of the commercial NIPT companies currently meet all the basic recommendations of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Click here for more information.)

NIPT can be done as of week 9. However, it is most often done after a positive NT scan or serum screening. Out of 100 babies with Down syndrome, this type of screening will identify about 99.

NIPT is more accurate than NT scans and serum screening for detection of Down syndrome. However, it is more expensive. It is not paid for by all provinces, nor by all private insurances.

Although NIPT is very accurate, both false positive and false negative results can occur. Therefore, those who wish to end a pregnancy after a positive NIPT need to confirm the result with prenatal diagnosis.

Learn more on NIPTIn addition to Down syndrome, NIPT can also test for other conditions where the fetus has an extra chromosome, including Patau syndrome and Edwards syndrome. It can also test for conditions caused by a nontypical (extra or missing) numbers of sex chromosomes: Klinefelter syndrome, Turner syndrome and triple X syndrome.

Typically, females have two X chromosomes (XX) and males have one X chromosome and one Y chromosome (XY). Any other number of sex chromosomes will lead to syndromes in the fetus that vary from mild to life-threatening. People who receive a “positive screen” for one of these less-common syndromes will be offered follow-up prenatal diagnosis and medical information specific to that condition. NIPT cannot find neural tube defects (NTDs) that can be found by serum screening. Most neural tube defects are identified by ultrasound in the second trimester.

Although NIPT can be performed as early as week 9 or 10, many professional associations recommend using it only in pregnancies with high probability of having a condition. A pregnancy is considered “high probability” (sometimes referred to as “high risk”) when:

-

-

- Another screening test, such as screening serum and/or a nuchal scan gave a “high-probability” result.

-

Or

-

-

- The pregnant woman will be 40 years old or more at the expected time of delivery.

-

Or

-

-

- There is a personal or family history of a condition that can be found by NIPT.

-

Some Canadian provinces currently do not cover the cost of NIPT through public healthcare. Ontario, Manitoba, British Columbia, Quebec, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador have added NIPT to their prenatal screening programs for high probability pregnancies. NIPT is available in private clinics across Canada for high probability and low probability pregnancies. It may also be available as part of clinical trials in some locations.

NIPT gives results that are more reliable than nuchal scans and serum screening. In high probability pregnancies, NIPT detects 99 out of 100 fetuses that have trisomy 21, 18 or 13.

However, NIPT is not as certain as a diagnostic test. This means that it can give a “positive result” even if the baby does not have the condition. This is called a “false-positive”. False-positives happen frequently, especially in low probability pregnancies. Because of this, a diagnostic test (CVS or amniocentesis) is recommended for:

-

-

- People who want to be as sure as possible about the result.

- People considering terminating the pregnancy after a positive NIPT.

-

However, false-negatives (a negative screen when the fetus actually has a trisomy) are rare with NIPT.

In about 1% to 8% of cases the test does not give a result. In these cases, the chance of a chromosomal trisomy, especially trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome) and trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome) is increased and the NIPT should be repeated or other tests can be used.

Prenatal diagnosis

Prenatal diagnosis is a test that tells you if your baby has Down syndrome or not. It can also tell you if your baby has other chromosomal abnormalities not detected by screening, such as rare trisomies and chromosomal rearrangements. There is a small risk of losing the baby with prenatal diagnosis. It requires collecting samples from inside the womb with a needle. The two types of prenatal diagnosis are amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling (CVS).

If you have a positive screen, you will be offered prenatal diagnosis. However, this does not mean that you have to do it. Doing prenatal diagnosis or not is a personal choice. Some people want to know as much as possible. Some people prefer not to know in advance. For some people, the information is worth the risk. For others, it is not.

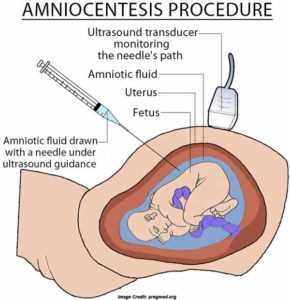

Amniocentesis

To do amniocentesis, the doctor collects liquid from inside the womb with a needle. The needle goes through the belly. The liquid is called “amniotic fluid”. It contains DNA from the baby. It can be done from week 15 of the pregnancy. There is a small risk of pregnancy loss (miscarriage) after amniocentesis. The risk is between 0.2% and 0.5% (1 in 500 to 1 in 200). It can happen whether or not the fetus has Down syndrome.

Amniocentesis is the most common type of prenatal diagnostic test. It involves collecting a small sample of amniotic fluid from the uterus, using a fine needle that is inserted through the pregnant patient’s abdomen, under ultrasound guidance. This fluid contains fetal cells from which chromosomes, or DNA, can later be analyzed. Amniocentesis can be done from week 15 of the pregnancy.

Advantages:

Amniocentesis provides a diagnosis (definite result), as opposed to a probability, or a likelihood/chance. It is more widely available than CVS and it fails in less cases than CVS.

Disadvantages:

Discomfort can be felt from the needle insertion. Amniocentesis involves an increased risk of miscarriage estimated at 0.2-0.5% (1 in 500 to 1 in 200). Other possible complications include pain, cramps, bleeding, fever, and loss of amniotic fluid.

Compared to CVS, the test is done later in the pregnancy, and analyzing the sample may take longer (2 to 4 weeks), although results can be obtained faster (4-6 days). This leaves less time for decision-making. If someone chooses to terminate the pregnancy because of the results of amniocentesis, the termination would occur later in the pregnancy.

After the amniocentesis, it is recommended to rest for 24 hours.

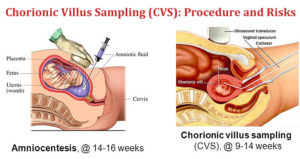

Chorionic villus sampling (CVS)

To do CVS, the doctor collects cells from the placenta, called villi, with a catheter. They contain DNA from the baby. The catheter goes through the belly or inside the vagina. CVS can be done between 11 and 14 weeks of pregnancy. There is a small risk of pregnancy loss after CVS. The risk is 0.5% to 1%. In 200 CVS, 1 or 2 pregnant patients lose their baby. It can happen whether or not the fetus has Down syndrome.

Chorionic villi are little branches in placental tissue that reach out in the wall of the mother’s womb to help the flow of blood between the mother and fetus. Therefore, villi are the placental structures that are most easily accessible from the outside. CVS consists of collecting a small piece of villi with a needle or catheter. The procedure is guided by ultrasound and may be done through the abdomen or vagina. The actual procedure takes less than one minute but it takes overall approximately 10-20 minutes including the preparation. It is performed between weeks 11 and 14 of pregnancy.

Advantages:

CVS provides definitive results, as opposed to a probability or a likelihood/chance, early in the pregnancy, which leaves more time for decision-making about the pregnancy. Results are usually provided within 2 weeks.

Disadvantages:

There is an increased risk of miscarriage estimated at 0.5-1% (1 in 200 to 1 in 100). Discomfort or pain can be felt from the needle insertion. Other possible complications include pain, cramps, bleeding, fever, and loss of amniotic fluid. Test failure: in 1 to 2% of cases, the results may be inconclusive due to the presence of maternal tissue in the collected sample or other technical problems. In these cases, either a new CVS or an amniocentesis could be offered.

After the procedure, it is recommended to rest for 24 hours.

References

See referencesACOG (2016). “Screening for Fetal Aneuploidy.” American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstetrics & Gynecology 127(5). e123-e137.

Cartier, L., L. Murphy-Kaulbeck, R. D. Wilson, F. Audibert, J.-A. Brock, J. Carroll, L. Cartier, A. Gagnon, J.-A. Johnson, S. Langlois, L. Murphy-Kaulbeck, N. Okun and M. Pastuck (2012). “Counselling Considerations for Prenatal Genetic Screening – SOGC Committee opinion.” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada 34(5): 489-493

Marteau, T. M., J. Kidd, R. Cook, S. Michie, M. Johnston, J. Slack and R. W. Shaw (1991). “Perceived risk not actual risk predicts uptake of amniocentesis.” Br J Obstet Gynaecol 98(3): 282-286.

MSSS (2010). “Programme québécois de dépistage prénatal de la trisomie 21 — Cadre de référence.” Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Gouvernement du Québec. http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/document-000783/.

MSSS (2020). Programme québécois de dépistage prénatal de la trisomie 21. Gouvernement du Québec, Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec,. 20-931-014F. https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/fichiers/2020/20-931-04F.pdf

MSSS (2023). Programme québécois de dépistage prénatal. Élargissement de l’offre. Guide informationnel destiné aux professionnels de la santé. Document provisoire. https://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/professionnels/documents/pqdp/Formation_professionnels_COVID19_2023-04-05.pdf

Prenatal Screening Ontario. (2021). “Prenatal Screening Ontario.” Government of Ontario http://prenatalscreeningontario.ca/.

Slovic, P. (1987). “Perception of risk.” Science 236(4799): 280-285.

Wilson, K. L., J. L. Czerwinski, J. M. Hoskovec, S. J. Noblin, C. M. Sullivan, A. Harbison, M. W. Campion, K. Devary, P. Devers and C. N. Singletary (2013). “NSGC Practice Guideline: Prenatal Screening and Diagnostic Testing Options for Chromosome Aneuploidy.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 22(1): 4-15.

Wilson, R.D., et al., Prenatal Diagnosis Procedures and Techniques to Obtain a Diagnostic Fetal Specimen or Tissue: Maternal and Fetal Risks and Benefits – SOGC Clinical practice guideline. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 2015. 37(7): p. 656-668.